# Introduction

# Modularization candidates

One of the great dividends of building upon opinionated structures is that it decides on a solution to the architectural problem for the developer. With that out of the way, they are left to figure out higher-level problems. For web applications, those higher-level problems are usually services.

This doesn't mean every application should be structured in the same manner. The idea is that the number of ways to poorly structure an application far outnumber proven ways to build applications that are easier to maintain. It takes a level of thought that can be expensive for some. For these set of developers, it helps to condense proven designs into reusable frameworks, in order to take that responsibility away from them. In our case, modules should not be shoe-horned into every project simply because they exist or are considered a cool fad. They are better suited for:

Applications comprised of easily distinguishable domains.

AGILE settings where features/domains will likely be short-lived, activated and deactivated.

The detachable characteristic of modules means they can be developed and tested independently, benefit from having their own .env file, etc. More importantly, they can be integrated without risk of crumbling the existing project. To be clear, modules don't necessarily offer protection against breaking existing features after updating unrelated parts of the codebase. To solve that problem, you'd like to look at the appendix chapter for integrating new changes.

# Contents of a module

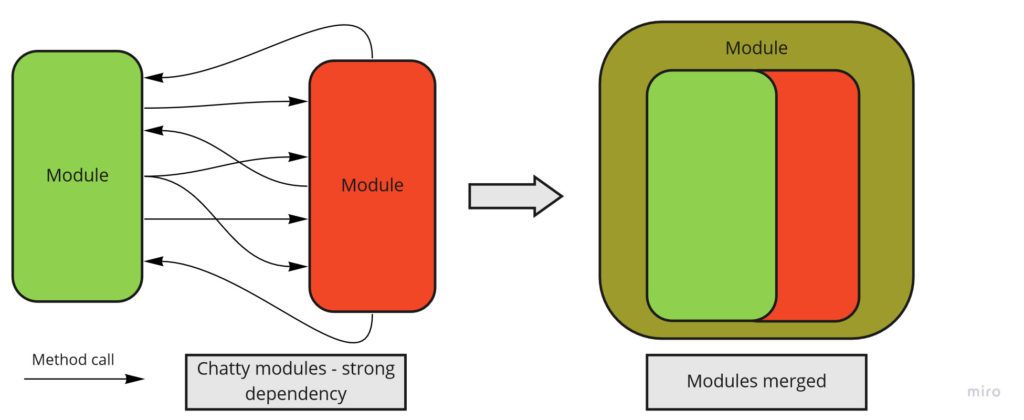

It's recommended that each module is an arrangement of classes pertaining to one database model or entity. A portable module can be extracted from the application where it was created, and still retain enough conceptual meaning to be plugged in another application or standalone. It's usually safer for concepts/domains to start out as separate modules dependent on each other, and only get merged into one when the interactions between them becomes more than trivial. If a coordinator in ModuleA is dominated by calls to different services borrowed from ModuleB that it depends on, it could mean they belong together.

(source: the internet)

(source: the internet)

It's a code smell not limited to modules alone but to classes as well, and is more commonly known as Inappropriate Intimacy.

Modules are not restricted to concepts that interact with each request, but can correspond to smaller programs/user-defined sub-components (such as aggregation robots), requiring more than one class, that occassionally performs some micro action on the main application.

# Creating a module

A Suphle module is a folder with some essential classes that are eventually connected to the rest of the application through the module's descriptor. They may be created by hand, although it's more realistic to use the following command for this purpose.

php suphle modules:create Products --module_descriptor="\AllModules\Products\Meta\ProductsDescriptor"

When run, the command above will transfer contents of the template folder, ModuleTemplate, to a new Products module, replacing namespaces, class names and their contents, generally mirroring source structure to appropriately match the newly birthed module. When present, the module_descriptor option causes component templates to be automatically installed after module creation.

Usually, ModuleTemplate will be customized to taste. If, however, your architecture of choice deviates from the default, your module template may reside away from the Suphle executable. In this case, its new destination should be communicated to the executable through its template_source option:

php suphle modules:create Products --module_descriptor="\AllModules\Products\Meta\ProductsDescriptor" --template_source=some/path

template_source expects an absolute path by default. When it's more convenient to supply a path relative to executable location, include the is_relative_source (or, the shorthand i) option to your recipe:

php suphle modules:create Products --module_descriptor="\AllModules\Products\Meta\ProductsDescriptor" --template_source=some/path --is_relative_source

In a similar vein, directory modules is created in can be changed from the executable's path to one passed in the destination_path option.

php suphle modules:create Products --module_descriptor="\AllModules\Products\Meta\ProductsDescriptor" --destination_path=some/path

Contents of ModuleTemplate are flexible and should match whatever dominant structure your modules start out with. For instance, its default contents contains a connected route collection, along with routing bits. This doesn't reflect a mandatory requirement for a valid module. The only reason for this is to facilitate bootstrapping new Suphle projects. A module that itself doesn't handle requests can afford to miss all the routing-related classes. But more importantly, such module should not be connected to the application as a standalone module.

# Connecting standalone modules

This refers to the composition that allows modules partake in the routing process for HTTP-based applications, or for command extraction in CLI-based applications. This congregation occurs at any sub-class of Suphle\Modules\ModuleHandlerIdentifier. In your Suphle installation, this sub-class resides under AllModules\PublishedModules. All our runners either consider this the entry point to your application, or the application itself. If you have any reason to change its name, remember to update it to this new name in those runners, as well.

As far you're concerned, the only method on this class worth extending is its getModules method. Here, we expose our list of modules using their descriptors as follows:

namespace AllModules;

use Suphle\Modules\ModuleHandlerIdentifier;

use Suphle\Hydration\Container;

use AllModules\{ModuleOne\Meta\ModuleOneDescriptor, ModuleTwo\Meta\ModuleTwoDescriptor};

class PublishedModules extends ModuleHandlerIdentifier {

function getModules():array {

return [

new ModuleOneDescriptor(new Container),

new ModuleTwoDescriptor(new Container)

];

}

}

By excluding any of the descriptors, perhaps while its module is still under development, the app is blissfully oblivious of all that module's contents -- events, routes, commands, etc.

The app composition above is enough for simplistic scenarios where there is no direct communication between any of the descriptors. It's also how all your modules will start out until you define their capabilities later on. As has already been established in several chapters across this documentation, direct calls should only be made to dependencies when they return a value. This allows new additions to evolve and be tested without tampering with/breaking the scope triggering their execution. It also doesn't pollute this scope with references not meaningful to it. This same rule of thumb applies to inter-dependent modules.

# Module inter-dependency

This becomes imperative when sharing data or functionality between modules within the same application. PHP doesn't have the concept of packages yet. This means, you can still comfortably reach into modules, manipulating them as you deem fit. However, this is strongly discouraged. Each module must provide the interface it's an implementation of. The advantage of depending on a module's interface over its internal services are manifold:

Interfaces offer a uniform platform for listing the capabilities this module offers its consumers. It doesn't have to mention everything the module itself does -- only the parts controllable from/shareable to the outside world.

We can move a module in-between applications without coupling to specific dependency implementations.

Modules can be tested by stubbing out the interfaces of modules they are dependent on.

Suphle doesn't enforce boundaries between modules. For that, you'll need to write a startup filter that revolts when a dependency within the root AllModules namespace doesn't conform to that of the penultimate parent namespace of the evaluated class.

# Defining producer modules

Modules yet to contain any data or functionality worth sharing can be represented by blank interfaces. Suphle provides one of such generic interfaces, Suphle\Contracts\Modules\ControllerModule. This placeholder interface is in turn implemented by a blank class that will be received by any dependent module consuming the new one. This integration is automatically done for all new modules.

When the new module eventually defines shareable functionality, it can then be defined on its own custom interface. The default module template will create this interface for you. So, if you intend to modify the template structure, do remember to take this detail into account.

Modifications to this interface can then be done as with any other interface.

namespace ModuleInteractions;

interface ModuleTwo {

public function getBarValue (int $newCount):int;

public function doFoo ():void;

}

By the namespace used and its location, you may observe that module interfaces reside outside the implementation created for them. The implementations can be removed or replaced at will. But consumers will always rely on the contract on the interface.

ModuleTwo, above, is a simplistic interface in that it only deals with primitive types. Note that this is not always the case in the real world.

Usually, you'd want your module to be consumed directly from a coordinator in the dependent module instead of proxying calls to it using additional services. In this case, it'll be wise for the module's interface to extend Suphle\Contracts\Modules\ControllerModule. Suphle uses this measure to dissuade direct consumption of the implementation classes. Should you attempt to inject a random module interface into a coordinator, as with any other unknown class, it will throw a Suphle\Exception\Explosives\DevError\UnacceptableDependency exception.

# Integrating module interfaces

These are steps to be taken to ensure both the producer itself and its possible consumers are aware of the interface created above.

Internally, its interface should be bound like other simple ones:

namespace AllModules\ModuleTwo\Meta;

use ModuleInteractions\ModuleTwo;

class CustomInterfaceCollection extends BaseInterfaceCollection {

public function simpleBinds ():array {

return array_merge(parent::simpleBinds(), [

ModuleTwo::class => ModuleApi::class

]);

}

}

ModuleApi has a regular implementation to boot:

namespace AllModules\ModuleTwo\Meta;

use ModuleInteractions\ModuleTwo;

class ModuleApi implements ModuleTwo {

public function getBarValue (int $newCount):int {

return $computatedResult;

}

public function doFoo ():void {

//

}

}

Afterwards, compatibility with this interface/contract is announced to other modules using the Suphle\Contracts\Modules\DescriptorInterface::exportsImplements method.

namespace AllModules\ModuleTwo\Meta;

use ModuleInteractions\ModuleTwo;

class ModuleTwoDescriptor extends ModuleDescriptor {

public function exportsImplements():string {

return ModuleTwo::class;

}

}

Other modules will reference this one using this interface. If in any of those references, an incompatible implementation is given, a Suphle\Exception\Explosives\DevError\InvalidImplementor exception will be thrown and prevent server build.

# Receiving module dependencies

This is divided into two two phases:

- Declaring consumer dependencies.

- Setting module implementations.

# Declaring consumer dependencies

We use an explicit key-value pair to dictate what dependency type is being imported along with its complimentary concrete. This enables clarity in definition of dependencies to be fulfilled before each module can be whole. Think of it as an argument list but for modules. Having this kind of boundary foils indiscriminate access to modules not explicitly depended on.

These dependencies are enumerated on the Suphle\Contracts\Modules\DescriptorInterface::expatriateNames method.

namespace AllModules\ModuleTwo\Meta;

use ModuleInteractions\{ModuleOne, ModuleTwo};

class ModuleTwoDescriptor extends ModuleDescriptor {

public function exportsImplements ():string {

return ModuleTwo::class;

}

public function expatriateNames ():array {

return [ModuleOne::class];

}

}

# Setting module implementations

To fill in the blanks on expatriateNames, we'll revisit our app composition, modifying it to reflect new requirements.

namespace AllModules;

use Suphle\Modules\ModuleHandlerIdentifier;

use Suphle\Hydration\Container;

use AllModules\{ModuleOne\Meta\ModuleOneDescriptor, ModuleTwo\Meta\ModuleTwoDescriptor};

use ModuleInteractions\ModuleOne;

class PublishedModules extends ModuleHandlerIdentifier {

function getModules():array {

$moduleOne = new ModuleOneDescriptor(new Container);

return [

$moduleOne,

new ModuleTwoDescriptor(new Container)->sendExpatriates([

ModuleOne::class => $moduleOne

])

];

}

}

In larger apps, some of the modules will tend to have enough dependencies to crowd the getModules method. In such case, don't hesitate to build them from the comfort of dedicated methods, only using instance variables on getModules.

While building your application, a verification is performed to compare implementations with the consumer's expatriateNames. Any one that doesn't match this list will cause an Suphle\Exception\Explosives\DevError\UnexpectedModules exception to be thrown, preventing app from building.

# Dependency availability

Aside from coordinators, somewhere else module interfaces are likely to wind up is in the implementation class of a consumer; perhaps, for values computed by this module without necessarily being involved in a request's response. As with coordinators, the consuming module is free to inject it as it would with any other interface. Suphle will boot the modules and hydrate their implementation classes accordingly.

namespace AllModules\ModuleTwo\Meta;

use ModuleInteractions\{ModuleOne, ModuleTwo};

class ModuleApi implements ModuleTwo {

public function __construct (protected ModuleOne $moduleOne) {

//

}

public function getBarValue (int $newCount):int {

return $this->moduleOne->setBCounterValue($newCount);

}

public function doFoo ():void {

//

}

}

The above is a contrived example used to illustrate that dependencies are ready for use as early as possible. Modules shouldn't act as proxies to other modules, except when absolutely unavoidable.

Suphle app composition API is designed in a way to prohibit cyclical referencing. This sort of scenario may crop up in real life and is a legitimate one where proxy modules are inevitable. Solutions have been discussed in the circular dependencies section.

# Module booting

ModuleDescriptor's design sets it up for a sequential initialization process i.e. Container warming for basic operations such as route seeking; it's certainly more optimized to carry out those involved functionality only when a module's route collection matches incoming request. However, all modules are eagerly built immediately they're connected. Most importantly, this allows for wiring their individual event managers into the grand app scope and recursively booting module dependencies that aren't present on the outer, routable scope.

# Guidelines on data sharing

# Data sharing format

The purpose of the data being shared should determine what format it is being served in. Data intended for use in the computation of a consumer can be served in its raw format, while data needed for to be plugged into a view template may benefit more from micro front-ends to achieve a higher degree of modularity.

# Sharing tangible artifacts

Modules are structures intended for reuse in exposing data or functionality for manipulating data; otherwise called non-tangible artifacts. If you find yourself needing to share or extend tangible resources (classes such as route-collections, middleware, etc), it's an indication to convert them into component-templates. The author of the template will still have majority of the say over the abilities accessible to the consumer.

# Testing modules

A lot of functionality provided in Suphle cannot be tested independently without them existing in a module e.g. the routing experience or request handling. The sort of tests are called module-based tests. They are all expected to extend the Suphle\Testing\TestTypes\ModuleLevelTest base test class. The most basic module-level test will look like this:

namespace AllModules\ModuleOne\Tests\SomeDomain;

use Suphle\Hydration\Container;

use Suphle\Testing\TestTypes\ModuleLevelTest;

use AllModules\ModuleOne\Meta\ModuleOneDescriptor;

class SomeDomainTest extends ModuleLevelTest {

public function getModules ():array {

return [new ModuleOneDescriptor(new Container)];

}

public function test_something_module_specific () {

//

}

}

The getModules method allows for connecting as many modules as are relevant to this test. It's then on this sub-class that you'll use whatever trait is relevant to the specific functionality you intend to test.

# Obtaining module reference

Suphle's testing traits offer high-level access to observing the functionality in question. Where low-level reference to the module interface's implementation is required at the modular layer, you can use the getModuleFor method as follows:

public function test_given_module_implementation () {

$this->getModuleFor(ModuleTwo::class)->doFoo(); // when

// then

}

For internal tests within the module itself, a regular test will suffice, especially when the implementation class doesn't inject other modules. getModuleFor is only required when retrieving an implementation after the module has been booted.

# Unit testing a module

During the module booting sequence, all bound objects or interfaces are wired in as they were defined. In test environments however, it may be more suitable to replace those objects with test doubles. This replacement should be carried out before the test commences so any consumer they have can read them i.e. as early as possible.

Object doubling is carried out using a special Container received in a callback at the 2nd argument to the replicateModule method.

# Binding automatic doubles

What can be bound here can range from doubles for interfaces to concretes and what have you. Suppose we wish to configure our module to test a route collection other than the one actually bound to the module, it'll be done as follows:

use Suphle\Contracts\Config\Router;

use Suphle\Testing\{TestTypes\ModuleLevelTest, Proxies\WriteOnlyContainer};

use AllModules\ModuleOne\{Routes\Auth\AuthorizeRoutes, Meta\ModuleOneDescriptor, Config\RouterMock};

class SomeDomainTest extends ModuleLevelTest {

protected function getModules ():array {

return [

$this->replicateModule(ModuleOneDescriptor::class, function (WriteOnlyContainer $container) {

$container->replaceWithMock(Router::class, RouterMock::class, [

"browserEntryRoute" => AuthorizeRoutes::class

]);

})

];

}

public function test_something_module_specific () {

//

}

}

The call to replaceWithMock will create a positiveDouble for RouterMock and bind it to the Container given to ModuleOneDescriptor, and finally return an instance of the given descriptor. The double can equally be mocked by passing mock arguments as the 4th argument:

$this->replicateModule(ModuleOneDescriptor::class, function (WriteOnlyContainer $container) {

$container->replaceWithMock(SomeService::class, SomeService::class, [], [

"method" => [1, [$someArgument]]

]);

})

The 5th argument to replaceWithMock allows the double to be created using negativeDouble instead.

$this->replicateModule(ModuleOneDescriptor::class, function (WriteOnlyContainer $container) {

$container->replaceWithMock(SomeService::class, SomeService::class, [], [], false);

})

# Binding custom doubles

On occasions warranting a pre-configured object or an actual instance as opposed to its double, we'd rather use the replaceWithConcrete method.

$this->replicateModule(ModuleOneDescriptor::class, function (WriteOnlyContainer $container) {

$container->replaceWithConcrete($sutName, $this->configureInstance());

});

These methods are expected to tame the janky practice of using $this->modules[0]->getContainer()->whenTypeAny inside the test body.

They all support any form of reference type creation except using the replaceConstructorArguments method. This double-creator requires the presence of a Container, and none is ready until all modules are successfully built.

There is but one exception to build-phased binding: binding mocks that throw exceptions. These do not work because of the manner in which flow control propagates. When execution is disrupted by an exception, further evaluation is abandoned, including any mocks recorded prior to test method commencement. The runner will not resume by verifying those mocks after execution is terminated, since it could (or could not) mean execution didn't even get to the location of those objects.

Let's look at a sample build-phase mock below:

protected function getModules ():array {

return [

$this->replicateModule(ModuleOneDescriptor::class, function (WriteOnlyContainer $container) {

$container->replaceWithMock(Router::class, RouterMock::class, [

"browserEntryRoute" => SomeCollection::class

])

->replaceWithMock(SomeService::class, SomeService::class, [], [

"awesomeMethod" => [0, []] // then

]);

})

];

}

public function test_some_operation_expected_to_pass () {

//

}

This mock is verified at the end of the test, as long as the ensuing action does not throw any exceptions. If it does, the test will error out. If the exception is deliberate and you wish to verify both the mock and the exception, the mock must be attached to the Container before execution commences, usually, the massProvide method for binding.

public function test_some_operation_expected_to_fail () {

$this->expectException(ExceptionName::class); // then 1

// given

// ...some preconditions

$this->massProvide([

SomeService::class => $this->positiveDouble(

SomeService::class, [], [

"awesomeMethod" => [0, []] // then 2

]

)

]);

// when

// ...trigger some action

}

# Doubling module dependencies

When we require functionality beyond the scope of a module but don't have access to its ready implementation yet, or when a given implementation is broken and impedes development of another one, instead of declaring a dependency on it through expatriateNames, the producing module should be stubbed out as a regular interface. That way, building the micro application for the test won't fail.

$this->replicateModule(ModuleTwoDescriptor::class, function (WriteOnlyContainer $container) {

$container->replaceWithMock(ModuleOne::class, ModuleOne::class, $stubs);

});

The complete module setup should only be used when testing the system's integration as a whole and when available implementations are stable.

When the double is mocked, exercise caution in ensuring only one copy is created. It's easy to get carried away when multiple modules are bound with similar configuration. The pitfall opens when this callback implicitly creates a mock for each module like so:

protected function getModules ():array {

$bindsCommands = function (WriteOnlyContainer $container) {

$container->replaceWithConcrete(

$this->sutName, $this->someMockFactory()

);

};

return [

$this->replicateModule(ModuleOneDescriptor::class, $bindsCommands),

$this->replicateModule(ModuleTwoDescriptor::class, $bindsCommands)

];

}

When this micro-app is built, the callback will be executed twice for both modules. This will lead to the surprising presence of phantom mocks expecting a call to have or have not occured -- in short, an expectation contrary to the single callback visible.

If you have two identical module configurations, a single mock can either be stored as an instance variable (instead of a factory producing for each module), or for the sake of clarity, duplicate the callback for both module definitions.

# Disabling doubled decorators

The modules built from replicateModule will trigger their internal decorators. If you're debugging something where a decorator is interferring with the test, or you have some other reason to bypass the decorators, you can pass true as the 3rd argument to replicateModule

$this->replicateModule(ModuleTwoDescriptor::class, function (WriteOnlyContainer $container) {/**/}, true);

# Stubbing the descriptor

The most common need for stubbing the descriptor itself during the build-phase is for temporary replacement of its interface collection. Stub methods can be given to the module replicator byspassing an array as its 4th argument.

protected function getModules ():array {

$interfaceCollection = new class extends CustomInterfaceCollection {

public function simpleBinds ():array {

return array_merge(parent::simpleBinds(), [

SomeInterface::class => ItsConcrete::class

]);

}

};

return [

$this->replicateModule(ModuleOneDescriptor::class, function(WriteOnlyContainer $container) {

// some bindings

}, false, [

"interfaceCollection" => $interfaceCollection::class

])

];

}

# Retrieving routed container

Occasionally, behavior not covered by dedicated test traits can only be tested by manually examining affected objects. This is often a matter of injecting a double or instance and observing that as we have seen in preceding sections. However, some requirements call for further scrutiny. When this is the case, we'd have to read that object from the module that handled request using the getContainer method.

public function test_read_container_after_routing () {

$this->get("/segment"); // when

$this->getContainer(); // read or use for some other purpose

// then

}

When used before routing occurs, this method will return the first container in the list of given modules.